By Aaron Gerry

Frustration can be a powerful motivator, in climbing and in business. For some climbers, existing climbing gym options don’t meet their needs, leading them to create their own facility to fill the gap. Most start for-profit businesses, some develop nonprofits, and still others organize cooperatives. This article focuses on the third group.

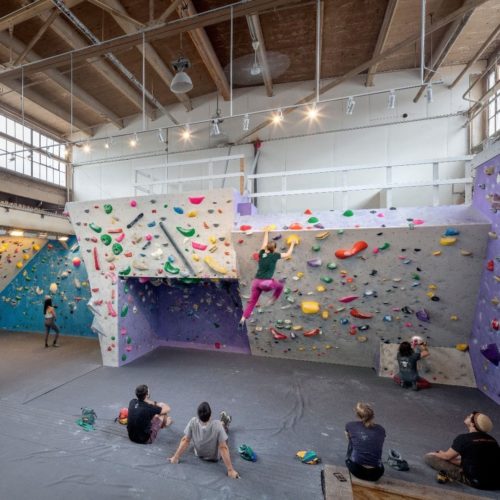

Cooperative climbing gyms typically arise where no indoor options exist or a small collective of dedicated climbers desire a training-specific space away from the crowds of larger facilities. While the gyms begin from a simple premise, survival in a fast-growing industry is anything but elementary.

Here’s a look at how several gyms with cooperative-based business models across the U.S. and Canada – from Yellowknife to North Conway, Silverthorne to the Twin Cities – got their co-ops off the ground, why this model was chosen, and lessons gleaned along the way.

Cooperative in Spirit, if not in Structure

In their simplest form, cooperative climbing gyms are businesses that are member-owned and democratically run. Each member has an equal share in the company and an equal vote for decisions (one member, one vote). Generally, day-to-day operations are managed by a board of directors, comprised of and elected by the members. Another core principle of cooperatives is that they are uniquely member-centric. Historically, gyms have served members by keeping prices down, allowing 24-hour access, or even paying out dividends.

“Over the last ten years we’ve seen an increase in cooperatives,” begins Mark Fick, the Director of Lending at Shared Capital Cooperative, a Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) that provides financing to cooperative businesses throughout the U.S. “A lot of it was triggered by the recession [ten years ago], and a growing frustration among people that are employed in lower wage jobs, who have little say in how the business is run or how they are treated.”

How do cooperatives differ from traditional for-profits and nonprofits in these respects? While employees of for-profit companies can own equity in the form of stock, they do not have equal ownership nor decision-making input. Cooperatives differ from traditional nonprofits because a profit may be earned and redistributed to members. Cooperatives, as a for-profit, have broader opportunities to make money than nonprofits and are not tax-exempt organizations. Employees of nonprofits generally do not have equal ownership or decision-making input, which is fundamental to cooperatives.

However, laws regarding incorporation as a cooperative vary by state and, in some states, incorporation as a cooperative is not an option. Of the climbing gyms interviewed, only two gyms are officially classified as cooperative business entities. The other gyms interviewed were either previously registered as cooperatives or currently operate in the spirit of a co-op; they have hints of democratic values and a focus on members built into the structure. These gyms receive consideration in this article as well, since takeaways from their experiences can still be valuable for a gym considering a cooperative business structure.

A Model for Smaller Markets

“For many years, the community has been grumbling that there is no climbing gym here,” begins Chelsea Kendrick, one of the founding members of the Mount Washington Valley Climbers Cooperative (MWVCC) in North Conway, New Hampshire. “We have to drive 1.5 hours to the nearest gym.”

The Mount Washington Valley, with a cumulative population of just 20,000 people in the region, currently lacks a commercial climbing facility. The MWVCC gym, which is currently in the fundraising phase, will be a 2,000 sq. ft. facility with 1,200 sq. ft. of climbing wall space optimized for training purposes.

“I’m friends with a for-profit gym owner,” continues Kendrick. “They had looked at the [area] as a potential expansion location but decided it wasn’t viable [for their business model].”

The same phenomenon has occurred in Colorado, considered by many to be the climbing capital of the U.S. Kent Sharp, one of the founding members of Summit Climbing in Silverthorne, Colorado notes how the first iteration of the gym – a for-profit business – failed:

“We’re a small resort town with a total population of about 20,000 residents, two hours west of Denver. The gym opened in the early 2000s but the climbing community just wasn’t big enough to support it and they went out of business. We decided to re-open [with a cooperative-style model knowing] we probably wouldn’t make money off it. Today, we have more members than the first owners and are only making $5k a year. There’s no way we could do this as a for-profit.”

Cooperative climbing gyms can succeed in smaller markets because they are often cheaper to start and maintain than larger facilities. Of the climbing gyms interviewed, the average startup cost was between $25,000 – $45,000. The gyms reduce costs in the early stages by relying on the talents of initial members, whether it was constructing the walls themselves, fundraising, or even designing their own customer management software.

Once up and running, cooperative gyms continue to save significantly on labor costs by being exclusively volunteer-run. At the Minnesota Climbing Cooperative (MNCC), members man the front desk one shift per week during “Open Hours,” when the public can climb, and the head setter puts in 4-40 hours per month, depending on needs.

Other facilities, like The El Dojo in Florence, MA, are unstaffed and have automated processes which reduce overhead. “If someone signs up, all the emails and waiver forms are automatically sent, and rent is auto-paid each month,” shares Tim Murphy, the General Manager. Members access the gym via keycards, they have free range to set routes, and are expected to clean the facility after use. Murphy says he puts in just 5-10 hours on average per month towards operating the facility.

“There isn’t that much to running our space,” he notes.

Specialization in Larger Markets

In larger markets with existing commercial climbing gyms, cooperatives have carved a niche for themselves by providing a focused training facility with a communal atmosphere.

The El Dojo, for example, was opened on the basis of simple, serious training. “There was a community of us who wanted to train hard and the local offerings did not provide that in an adequate way,” shares Pete Ward, who co-founded The El Dojo in 2007. “I came up climbing in the early 90s. The mecca was the School Room in Sheffield. We saw from that generation how strong you can get with a 45 [degree] wall, campus board, and some free weights. You don’t need that much stuff.”

The MNCC was started in Minneapolis–Saint Paul for a similar reason. Gym climbers in the area banded together to create a place where they could have more control over the climbing experience. “Early on, our only rules were: no birthday parties, no teen kids,” laughs Phaydara Vongsavanthong, one of the co-op’s founding members. “At the time, around 2009, there was only one commercial gym and it was mostly rope climbing. The place would get so crowded, we couldn’t get on the walls.”

Officially registered as a cooperative in 2011, the MNCC has grown from two dozen members to over 1,400. These days, being located in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis comes with competition: Now there are seven commercial gyms. However, Vongsavanthong identifies the added competition as a positive. Because the MNCC is a specialized training space and hub for serious climbers, the influx of commercial gyms nearby has increased awareness of climbing overall and sent more die-hards through their doors.

“Initially, we were concerned about competing,” shares Vongsavanthong. “We realized the larger gyms were going to introduce more people to the sport than we ever will, and that will help us; not everyone will like that style, or they will be looking for different things [like we were back in the day].”

The same power of specialization has been true for The El Dojo, which sustains its co-op-style gym alongside a commercial gym less than a 15-minute car ride away. “There’s something that drives a certain set of climbers to find their own community,” says Ward. “Those people may not feel super comfortable at a [commercial] gym.”

When members seek additional accoutrements from their gym, the cooperative can adapt. As membership grew at The El Dojo and MNCC, there was a call for more training tools and a larger space, respectively. In both cases, the communities at the gyms paved the way for member-funded renovations.

At the MNCC, profit from member dues was plugged back into the development of the facility. “Folks wanted more climbing surface,” notes Vongsavanthong. “That led to installing a better landing surface and refreshing the walls, all paid from our savings. The community built that. They are keeping it alive and running it.”

In 2018, members of The El Dojo were interested in purchasing a Moon Board and started a fundraising campaign to finance it. “Instead of one person paying $3,000 to build one in their house, members donated to help bring one to the gym,” says Murphy.

Limitations of Co-Ops

Cooperatives don’t work in all cases and locations. Obtaining loans can be difficult when starting out, there can be limitations to the growth potential of volunteer-run operations, and the persistent need for member involvement can lead to burnout.

The Yellowknife Climbing Club in the Northwest Territories, Canada eventually transferred operations of the cooperative-turned-nonprofit over to the city due to leadership and volunteer fatigue. “The model worked for four or five years,” says Eric Binion, who was involved with the nonprofit. “Eventually, the Board grew tired of running it, and there just wasn’t enough leadership interest to sustain it.”

Kristin Horowitz, COO of The Pad in San Luis Obispo, says being registered as a nonprofit was a limiting factor for obtaining bank loans. The gym began as a small collective before registering as a nonprofit, then ultimately incorporated as a for-profit business. “When we built our second location in Santa Maria, the bank needed a guarantor. Cal Coastal (a nonprofit public-benefit corporation that services the financial needs of small businesses) did an SBA 504 loan to help guarantee it. That was about the max of what a bank could do for a nonprofit, and it’s what prompted us to change structures. No bank was going to lend millions of dollars to a nonprofit with no collateral.”

Despite some success stories, cooperative climbing gyms account for only a tiny fraction of the climbing gym industry in North America. If you think a cooperative business model may be right for your gym, be sure to seek legal counsel on the matter first and conduct thorough planning for starting-up, the short-term and the long-term.

“It’s hard,” says Vongsavanthong of starting and running the MNCC. “But it is very rewarding.”

About the Author: Aaron is a climber and freelance writer. After years in startups, his life took a circuitous soul-searching path that included teaching entrepreneurship in Ghana, working on a farm, and traveling through Eastern Europe. Now he’s keen to climb and write more.

Climbing Business Journal is an independent news outlet dedicated to covering the indoor climbing industry. Here you will find the latest coverage of climbing industry news, gym developments, industry best practices, risk management, climbing competitions, youth coaching and routesetting. Have an article idea? CBJ loves to hear from readers like you!