Today’s guest is John McGowan. I don’t even know the single best way to describe John. Entrepreneur, business developer, old school climber but new school visionary, adventurer, all of the above. I will say this: If someone were putting together a list of the most important figures of the climbing gym industry of the past 35 or 40 years, basically as long as there has been some semblance of an American climbing gym industry, John McGowan would absolutely be one of the names on it. He has started businesses that have contributed immensely to key evolutions of the climbing industry, as you will hear about. In terms of his resume, he founded Boulder Rock Club in 1990. He and a business partner, Steve Holmes, then founded Eldorado Climbing Walls a few years after that. Later, he and Steve Holmes also started TRUBLUE auto belays. And more recently he was involved in founding Riversmith, which is a company that he will explain more about in the conversation.

Thank you Kilter and TRUBLUE for your support!

And thank you Devin Dabney for your music!

Timestamps

00:00 – Intro

03:27 – Finding gold

11:58 – McGowan’s climbing history and opening Boulder Rock Club

15:32 – The monthly membership model

17:56 – The early 90s climbing scene

23:26 – Routesetting in the 90s

29:03 – Transitioning from Boulder Rock Club to other businesses

32:59 – The importance of a partnership in starting a business

36:31 – Keys to founding a business that actually works

39:28 – McGowan’s current business, Riversmith

43:23 – Make it better, make it easier

48:46 – Passion projects as potential businesses

51:19 – McGowan’s contact info

52:17 – Closing

Abridged Transcript

BURGMAN: I heard a rumor that I hope is true, because I’d love to hear the story, that you discovered gold, which sounds to me like some sort of Indiana Jones-meets-prospecting type of situation. Can you confirm or deny this? And if you can confirm it, I am a captive audience.

MCGOWAN: Okay, well, I can confirm that. It’s sort of a weird part about my history. After college, I ended up ski-bumming over in Europe for a couple of years, and that led to sort of taking an interest in sailing. And I eventually ended up living in Cape Cod. After that, I bought a little sailboat; it was a little, 20-foot sailboat. One thing led to another and I eventually sailed it down to Venezuela. That led to some inland travel. And after traveling around a bit, I met a guy who was interested in dredging for gold down in Venezuela. Ultimately, four years later, I ended up dredging for gold. And that’s sort of what funded a lot of the climbing interests. So, you’re right with that one…

You said that the dredging for gold helped fund your initial forays into climbing business. Were you a climber at the time?

Yeah, I grew up in Colorado and had a high level of interest in climbing, and so down in Venezuela, I did quite a bit of climbing—more typically in the area that I was living at the time down there, bouldering. But I was definitely a passionate climber. Whenever I could get a hold of a climbing magazine, I would certainly just go through it cover to cover and was starting to read a little bit about the emerging business of indoor climbing, and that kind of got me to thinking. Having grown up around Colorado, I definitely looked at that as being sort of an epicenter for climbing at the time, and ultimately began my escape from Venezuela, thinking about building a climbing gym in Boulder. By the time I actually got back, that was kind of the thought process: “Well, I’m just going to first of all explore the business of climbing and understand what that’s about.”

At the time, there was probably less than ten climbing gyms across the country…As I was exploring these different gyms, I was looking at the different operations and most of them were actually sort of a pay-to-play type of scenario, where you bought a guest pass in essence. But what I started to sense was there was one gym that was sort of doing a membership-based business. This kind of led me in Boulder to starting to think about the business of climbing as sort of a fitness club, which was very fortuitous in the early days.

What I did is I started looking around at different fitness clubs, just interviewing different people. And that’s really how I came across my [business] partner at the time, Scott Woodard. Scott and Karen Woodard at the time were running Boulder’s Pulse Fitness Clubs. And fortuitously enough, one of their fitness clubs—I think they had three of four around Boulder—had an adjacent space that was vacant in a building that Scott Woodard controlled. I presented Scott with my idea: “I really see the parallel of this being a great tie-in for fitness.” That led to Scott and I partnering up and starting the Boulder Rock Club.

Tell me about how you rolled out the initial membership structure and how people responded to that, because that would have been, as you just explained, pretty innovative for the time.

It was interesting, and I can’t say that we can claim sole ownership of that idea. However, most of the [climbing] gyms at the time were doing sort of a guest-pass scenario. There was a little teeny climbing gym that existed in Boulder, actually, when we started. It was at CATS Training Center, which was a gymnastics facility. They were a good example; they had perhaps 40 or 50 people climbing there, mostly just paying, I think, $5 a day in order to climb. And so, as I was kind of running the math on running a climbing gym, I couldn’t seem to make things work with just a guest pass scenario, especially given the seasonality of climbing. Ultimately, where membership came in, is really trying to sort of structure an annual plan in which we could survive both the winter, spring, summer and fall.

The [climbing] gyms that we toured, we did note that they were doing exceedingly well. Those couple of gyms that were doing this, they seemed like they were really cranking and they were growing a fast membership. So, as I was writing the business plan for the Boulder Rock Club, I projected that in our first year, even on our presale, we would probably start with about 100 members. As it turned out, when we got the idea out there before we opened, we sort of did a little bit of a police line inside the facility where people could come in and see the construction going on. While that was happening, we were selling memberships. Essentially, we launched with about 170 members or memberships sold, and ultimately that’s when we knew were on the right track of things.

The early 1990s. Can you give me an idea of the climbing scene?

I was of the belief that the only place that could support a climbing gym of that era was somewhere that had a high concentration of climbers. Later, I sort of evolved that theory into: “No, climbing is wherever there’s a large population, all of a sudden it can support it.” But in the early days there was this massive hidden climbing community around Boulder. What I remember is in the early days a lot of people had come in and there were these big-name climbers and just all these different people who were like, “No, I’ll never climb indoors.” They thought of it as almost the division line between sport climbing and trad climbing…And so the early dialogue that we had from folks was: “Yeah, this will never work.”

I remember one day, for example, Derek Hersey. I don’t know if you knew of Derek, but he was famous for climbing really hard climbs free solo at the time. So, he’d be out doing these insane things and just an amazing climber, an amazing spirit, and he was one of the few people who actually embraced it and basically said, “No, this is great because it’s creating this social environment.” Ultimately, we didn’t quite know what to expect in the early days. We didn’t know how important the social part of climbing was going to be. But what we saw within [those] probably first 18 months of being open is that, one by one, the people who were the most averse to what we were doing started embracing it and coming in—not so much to train, per se, but more for the social environment…

What were you doing for routesetting at the time? Because I know you mentioned the Paradise Rock Gym, and I know that Mike Pont, who’s someone you referenced, was working there as a routesetter for a time. And I know Christian Griffith was doing some routesetting, especially in the early 90s for Jeff Lowe’s circuit. Where were you finding routesetters? And if you could find them, were they getting any sort of training?

Paradise Rock Gym opened as we were just starting our construction, so they jumped us by a few months. And so, we’re starting to figure things out. I’m not sure how they got Kurt Smith and Mike Pont interested, but Brian Vandecrawl was the owner of Paradise Rock Gym. He was a very smart guy, and he really was the person who understood the power of routesetting. I certainly picked that up immediately from Brian, and it almost became sort of an escalation of who could set the best routes or who could recruit the best routesetters…We observed very early on that that is the product, the routesetting is the product. It’s certainly more important than almost anything that you’re going to do within a climbing gym. And so, you needed to invest heavily on that.

Now as far as actually getting people to do it, it was interesting because in the early days, even Mike and Kurt and Jimmy and all these guys, as great as they were at routesetting, they would typically migrate toward setting hard routes for themselves and their friends to climb. When they were setting a 5.13, they would set a masterpiece. But when it came to a 5.10, it was less than ideal. Ultimately, they became really adept at doing that, so I don’t want to say that they weren’t good at that, because they became excellent at it. But therein lay the real challenge of routesetting in the early days.

We found, for example, you could bring in the best climbers who could set a 5.13. They could set a 5.9, 5.10, 5.7…the 5.13 was going to be excellent, but the 5.7 was not going to be that great. And so, we thought, “Okay, well, what we’ll do is we’ll bring in 5.7 climbers to routeset the low end routes, or 5.10 climbers, or whatever.” But there was a distinct problem with that, in that those climbers were climbing 5.13 in three months. Just the act of routesetting at that level and climbing all your routes, it made them into hard guys immediately.

Ultimately, that sort of led to an evolution of investing really heavily in getting the routesetters to be in good alignment with the interests of the climbing gym to try to set really good creative routes, which I have to say is still probably one of the biggest difficulties in climbing gyms. If every climbing gym knew that this was of high importance, they might do things a little bit differently…

Can you talk a little bit more about that transition from starting Boulder Rock Club and then a second Boulder Rock Club, and then yourself going into building climbing gyms and the founding of Eldorado Climbing Walls as sort of the next step in the evolution of your own career? Right about 1995, if I remember correctly.

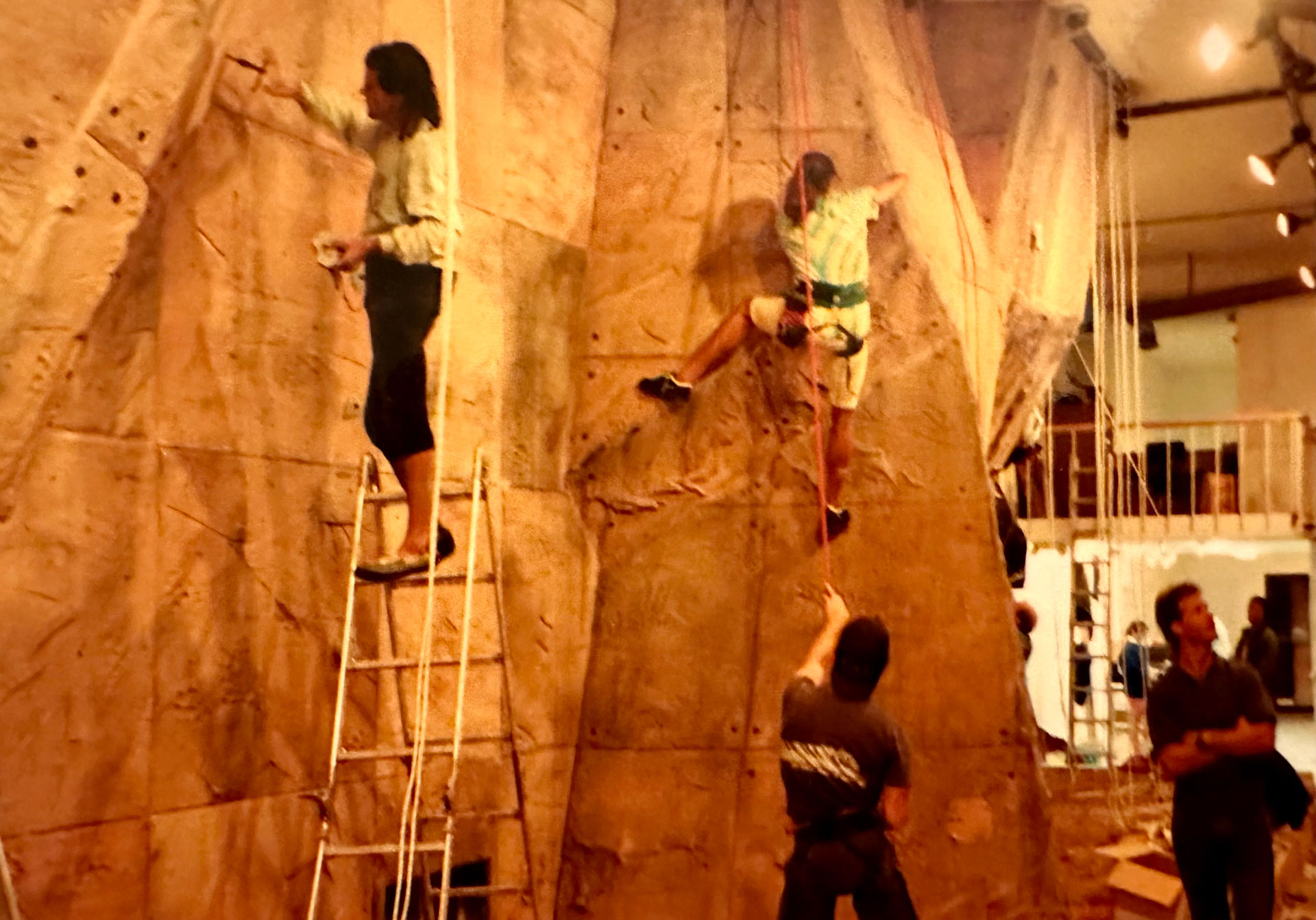

The entity that we hired to build our climbing walls for the first climbing gym, the first Boulder Rock Club, was a company called Radwall, and it was run by a guy named Wayne Campbell. He was an amazing artist. I have to say that their work was just impeccable; it was a beautiful type of work. But I’d been in construction before, and having kind of gone through that whole process, the way that they were building climbing walls, it was a panelized system that required you to frame up the entire climbing wall and then cut your panels, put them up to within a 32nd-of-an-inch tolerance, bring them down, then you would texture them, then you would hang them back up. It was this incredibly cumbersome process, which had some limitations as well. For example, you could use the seams. You could actually grab onto the seams or stand on the seams.

Ultimately, as I was kind of plotting the Boulder Rock Club 2, we were thinking, “There’s just got to be a better way to do this.” That led to experimenting around as we were coming onto building that. I remember building bouldering walls in people’s barns and just early ways to think about a different and faster way of building, a lower cost way of building, and a little more high performance…

Can you speak to the importance of partnerships? And maybe more specifically, what goes into making someone a good business partner?

With the right partner, you can actually build off of each other; it’s a momentum gaining kind of thing. And I would say with almost any business, there’s going to be a lot of effort in the early years, especially if you’re bootstrapping a company. That thing of having a partner to really build that momentum, I think it’s critically important, at least it has been within my career. As far as finding a good partner, it’s really interesting because I’ve talked to a million people who would say, “Well, I can tell you what you don’t want to do, and that is don’t ever do a 50/50 partnership. Those just don’t work. So, try to maintain controlling interest.” Ultimately, all of my partnerships have been 50/50 partnerships. I’ve had so many business people going, “Oh man, that’s insane. How in the world did that ever work? There are 10 million ways for it to fail.”

And I kind of thought back at my own career. For example, my partnership in Venezuela, actually that one did collapse. What happened down there was that I was working really hard and putting all this energy in, and my partner was just not. A 50/50 partnership under those terms is just not going to work. I later kind of thought about it in terms of: “Why don’t they work typically?” I think that, generally speaking, you have to both have a fairly high work ethic, and just trying to imagine how that can work over ten years, it’s sort of improbable in the first place. Second part of it is you have to have a similar type of intellectual capacity. You have to bring something to the table, and if one person’s really smart and the other one’s not, that also doesn’t work. So, there are a lot of reasons the 50-50 partnership doesn’t work. But I’ve found it in my life to be just a great system…

I’m sure we could devote a whole different podcast episode to it, but other than a good partnership, what are some keys to founding a successful business?

That’s another great question. I think ultimately my view on it is you don’t have to be the smartest, you don’t necessarily have to be the hardest working. You need to have, I think more than anything, a vision of where you want to go, and you have to have a fairly clear idea of where you’re starting from. Then it’s an incremental game. The way I think of any business, it’s not that you always make the right decision—that’s impossible. You’re going to make a lot of decisions in business and, incrementally, you want to make the right decision a little bit more often than the wrong decision. That incremental gain, in combination with having clarity of where you want to go, it means that you’re going to just walk slowly toward the finish line. All of these businesses, I think that’s the element. There was nothing that we did that was fast and easy. It was always just a slow, plodding thing.

I think another element to business success is exploring opportunities. I’ve had a lot of staff over the years who have said, “Wow, John, you’re so lucky because opportunities come your way. Boy, I just don’t know why they don’t come my way.” And I think just being receptive to ideas. My current observation is that everyone is bombarded with ideas all the time. Most choose not to see them, and some are like, “Huh, I wonder if that could work.” So that incremental movement forward…

Other folks who are starting businesses, if you’re not super well grounded, if you don’t know where you really are starting, it’s difficult to pick a direction. They end up working a little here, a little there, moving to the right, moving to the left, and not necessarily moving forward. So, I think it’s so important to be very well grounded within any business type of thing…

John Burgman is the author of High Drama, a book that chronicles the history of American competition climbing. He is a Fulbright journalism grant recipient and a former magazine editor. He holds a master’s degree from New York University and bachelor’s degree from Miami University. In addition to writing, he coaches a youth bouldering team. Follow him on Twitter @John_Burgman and Instagram @jbclimbs. Read our interview Meet John Burgman, U.S. Comp Climbing’s Top Journalist.