Spotlight on the 90s is a recurring column that explores the iconic climbing gyms of the 1990s—and examines how those facilities captured the essence of climbing and the ethos of the industry in that decade. Check back regularly for future installments of this ongoing series.

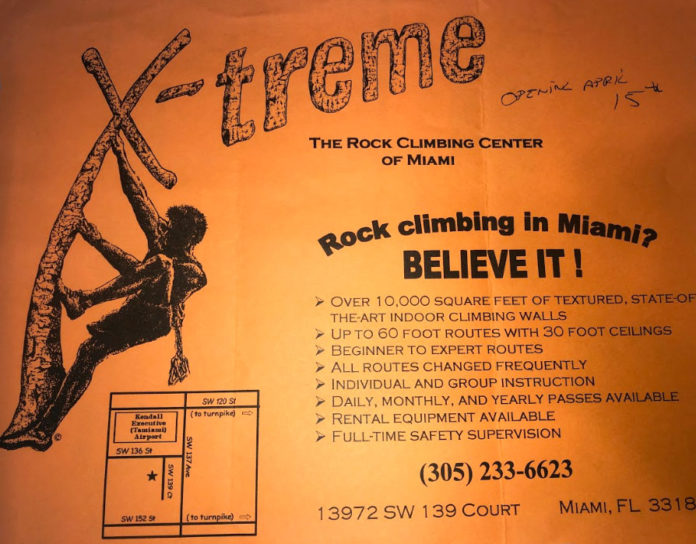

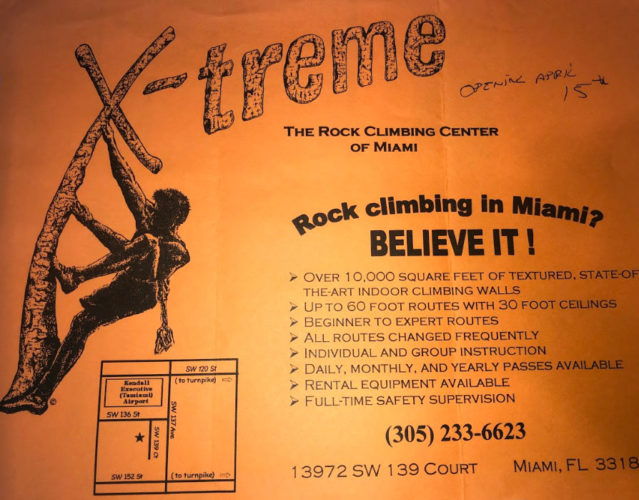

Gym: X-treme

Location: Miami, Florida

Opening Date: April 15, 1998

It is not hard for Derek Waggoner to identify the catalyst that led him to founding a climbing gym in South Florida. “Essentially it started with Hurricane Andrew in 1992,” he says without hesitation. More specifically, the hurricane’s destruction of a gymnastics school that Waggoner was operating in Miami at the time set off a fascinating chain of events. In the process, Waggoner would soon leave Florida altogether, start a new job as a financial advisor across the country, and dismiss climbing as an idiotic pursuit…only to fall madly in love with climbing and end up back where he started—in Miami.

But it all starts with Hurricane Andrew.

In fact, Waggoner was not alone in having his business—that gymnastics school—destroyed by the infamous hurricane system, which hit landfall in the early morning hours of August 24, 1992. According to estimates and after-the-fact calculations, by its end Hurricane Andrew caused $27.3 billion dollars in damages to people in and around Florida’s Miami-Dade County. It would prove to be the “costliest” hurricane in American history up to that point. Innumerable families were impacted and untold numbers of buildings and businesses were destroyed. Now, nearly 30 years later, Waggoner speaks of the hurricane’s force as if it was omniscient and deliberate—but that is only because the destruction was indeed so swift and widespread: “Hurricane Andrew came through and decided to take away all my clients, as well as the building and everything else,” Waggoner reflects.

In the wake of the destruction, Waggoner decided to pack up his belongings in South Florida and move to Colorado. He admits that he always wanted to “live the Rocky Mountain life.” But for Waggoner back then, this meant fishing. And he did fish a lot upon relocating to Colorado. He even encountered climbers at one point while out fishing but “thought it was the dumbest bunch of idiots I’d ever seen in my life that would go and climb a rock.” Yet, increasingly swept up in the Colorado outdoorsy milieu over the next couple of years, Waggoner eventually found himself taking an introductory climbing class at the Sport Climbing Center in Colorado Springs. After just a few minutes of belay instruction, Waggoner was hooked on climbing. Beyond that, he soon became friends with the owners of the Sport Climbing Center—he started climbing often with them too—and the idea of opening a climbing gym down south, in his home of Miami, soon sprouted.

A Hard Sell

The idea to open a climbing gym in Miami had come to Waggoner relatively quickly, but the necessary preparation and paperwork would be more methodical. One of the first challenges was obtaining financial backing for a climbing gym from some Miami banks. “I talked to three different banks and had two offers,” Waggoner recalls. “And it was a mixed bag—one bank was like, ‘You’re going to lose [everything], the others were just totally intrigued by it.”

Insurance paperwork was another challenge, as most companies and attorneys in South Florida were unfamiliar with the concept of indoor climbing as a business entity in the mid-1990s. As a solution, Waggoner—who had since moved back to Miami from Colorado—simply copied a release form that he had obtained from the Sport Climbing Center back in Colorado Springs. “I had no idea if it was valid or not, or if it would work in Florida,” he admits, although the paperwork would prove to be an effective and successful template for opening a Miami gym.

Beyond the legal logistics, Waggoner was increasingly convinced that climbing could be popular in South Florida—particularly because the sport had captivated him so quickly; he was living proof of climbing’s appeal. On top of that, Waggoner’s previous business contacts in the gymnastics world could help spread the word about his new Florida climbing gym endeavor, as climbing and gymnastics had crossover appeal that dated all the way back to gymnast John Gill’s pioneering of modern bouldering in the 1950s. There was also the sheer population of Miami. “I might be taking a smaller percentage compared to Denver or wherever, but the number base was there,” Waggoner explains of his mindset at the time. “Climbing was still semi-new to me, but I knew all people had to do was get a taste of it. Try it one time. If we could get people in the door, the gym would sell itself provided we didn’t scare them off.”

Waggoner’s previous connection to that climbing gym in Colorado Springs would prove beneficial again once a building was found in Miami. To design and construct the climbing walls in Florida, Waggoner used the same contractor (Ric Geiman) and company (Sport Climbing Concepts) that had built the walls of the Sport Climbing Center—and gave a directive to essentially “replicate” that Colorado wall design.

In total, Waggoner would create his climbing gym in Miami—X-treme—with a startup cost of $125,000. His brother, Kynan, would greatly help with the operations. The climbing walls, which Derek Waggoner describes as straightforwardly as “TJIs [joists], Simpson brackets, and some sheeting,” would measure 32 feet at their highest point. The interior would span 14,000 square feet, much of which was eventually covered with pea gravel as floor cushioning.

Nowadays, Waggoner is able to describe X-treme’s initial ambiance with honesty and the benefit of hindsight: “The lighting inside—it was just old lamps, typical gym of the ‘90s, back of a warehouse, dimly lit,” he says. But at the time of the gym’s opening in 1998, the newfound presence of a climbing gym in Miami—regardless of dingy lighting—was a big deal.

The Routesetting Epicenter

There was a period of learning that took place for Derek and his brother Kynan, as well as the customers when X-treme began its operations. As athletic and fit-conscious as many people were in Miami, the nearest outdoor climbing was in northern Georgia, nearly a day’s drive away, so there was a lot of initial unfamiliarity with the sport. “We started getting phone calls and people were asking, ‘Well, what else do you have to do [at the gym]?” Derek Waggoner remembers. “‘Do you have video games or bowling?’ How do you explain it? With the media at the time, we didn’t have Facebook or Instagram yet. It was newsprint and radio. How do you explain what’s inside a climbing gym?”

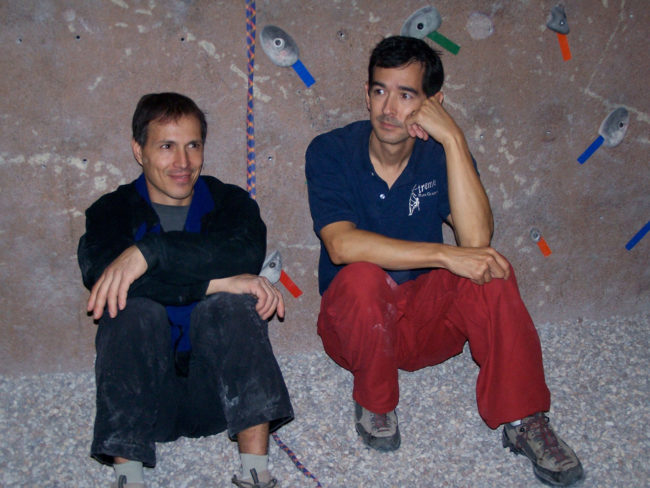

And Waggoner admits that he and his staff were “pretty green” as well, prompting a period of “trial-and-error” for properly running the gym. One of the most pressing issues was in matters of routesetting—and, specifically, the lack of trained routesetters available around South Florida. To solve the problem, within the first few months of X-treme operations, Waggoner flew back to Colorado to take a routesetting clinic hosted by the ASCF. At the clinic, Waggoner met Tony Yaniro—already among the most accomplished and distinguished routesetters in American history—and established a friendship that would result in Yaniro occasionally traveling down to Florida to set at X-treme.

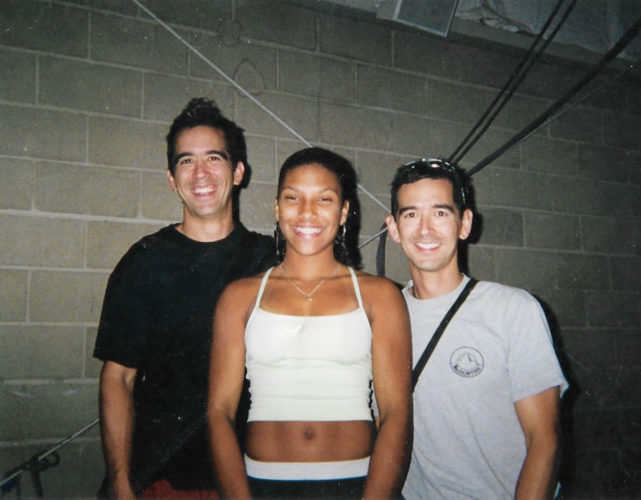

Another Colorado resident that Waggoner connected with was Kevin Branford. Although still just a teenager, Branford was one of the most accomplished American competition climbers. Branford, a national team member, had won the prestigious Tour de Pump series in 1994, participated in the climbing portion of ESPN’s first-ever Extreme Games (later rebranded the X-Games) extravaganza in 1995, and won his age division at the ASCF’s Junior National Championships in 1996. Waggoner first invited Branford to come down to X-treme and set for an ASCF regional competition. But Branford returned to Miami multiple times to teach clinics at X-treme and set non-competition routes.

“I started officially working for Derek when I was probably 20ish,” Branford recalls. “I would go down [to Miami] in the summertime when I was in college, and I would stay for three and a half months.”

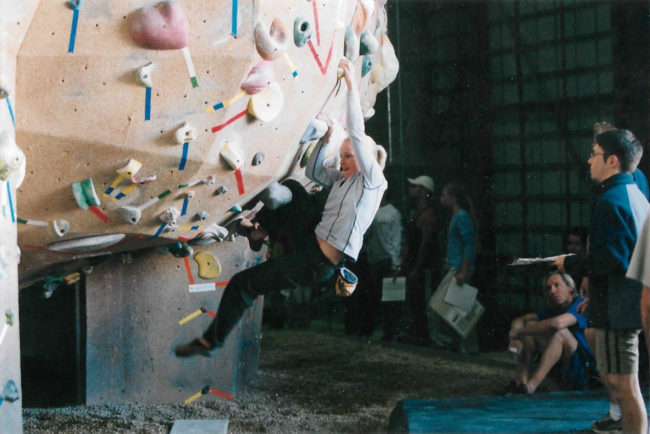

Completing this all-star crew was another young routesetter named Molly Beard. For a number of years, the team of Yaniro, Branford, Beard, as well as Derek and Kynan Waggoner, was among the most prolific and proficient in the country—venturing beyond X-treme and setting routes for National Championships, Junior National Championships, and competitions for the newly formed, kid-focused Junior Competition Climbing Association (JCCA). “There was no money, but all of us were committed to giving the kids the best, fairest competition possible,” says Beard. “It felt like we all could see what this fledgling [JCCA] organization could do and wanted to be sure it would happen. So, we worked unbelievably hard, suffered long hours, destroyed our skin and bodies, all with the driving goal to make it happen for the kids. I mean, Nationals now routinely use a crew of 12-15 routesetters. For several years it was just the four of us. So we bonded pretty hard over that. It made for some fun times setting when there wasn’t that crazy pressure and lack of time! And ice cream. We ate a lot of ice cream.”

In a sense, that same small squad of routesetters evolved the style of American routesetting that had been established approximately a decade prior. “We were all mentored by Tony [Yaniro], and his influence is undeniable,” Beard expounds. “His vision was to see a spread of placement based off of one or two points (therefore moves) between the competitors. Very finely tuned routes and forerunning was key. How different this was from previous years, I honestly don’t know: I only know stories secondhand. But hearing those stories of ridiculous bottlenecks, reachy routes, and flaming egos was enough…we understood the huge value of functioning as a team, of balancing out each person’s strengths and weaknesses to make the best competition routes possible. Modern holds were showing up at this time as well. I remember fighting over the VooDoo and Pusher stuff because it was so new and really good for forcing moves.”

A New Era

As the 1990s evolved into the 2000s, X-treme continued its operations—hosting a wide range of programming, from instructions to birthday parties. “Great exercise. Great fun. And it definitely beats pumping iron,” one writeup in the local Florida press proclaimed about the facility.

Competitions at the gym continued to be incredibly popular too. One particular event at X-treme had upwards of 50 sponsors; the title sponsor prize was a new mountain bike from Cannondale.

Particularly in hindsight, Waggoner sees the gym and all its events and programming as helping to give birth to a climbing culture in South Florida that still exists to this day. “I would say X-treme was the one that started the [climbing] community down there,” he says.

Waggoner admits that there were some climbers in South Florida before the founding of X-treme. He offers one anecdote about a few die-hards who used to illegally scale a lighthouse at Key Biscayne with climbing equipment. But it was X-treme that largely gave the disparate climbers in the city a sense of unification—an inclusive hub—and Kevin Branford agrees. “Derek basically had to build a market for [the gym] because people in Miami didn’t really know what rock climbing was,” Branford reiterates. “I think that was one of the things that drew me to liking Miami so much; I could help educate people and give them the best information that I had at the time about learning how to climb, about routesetting, about training practices. The people in Miami didn’t have any preconceived notions of how it was supposed to be.”

Derek Waggoner sold X-treme in 2013, and focused instead on a business of installing, inspecting, and repairing climbing walls on cruise ships with his other company, Xtr Services—through which he continued to employ Branford. Derek’s brother, Kynan, continued routesetting and eventually became the CEO of USA Climbing, a post he held through climbing’s formal inclusion in the Tokyo Olympics. In a unique twist, in April of 2019, Derek Waggoner and some business partners reacquired the gym that had started as X-treme. It is still in operation today as The Edge Rock Gym – Miami, although the interior (including the original lighting and flooring) has been significantly revamped and redone since the X-treme iteration.

Additionally, Waggoner currently operates the Gripstone gyms in Colorado and Arizona—fittingly with Tony Yaniro. But, in many ways, it all started with X-treme. “I had no idea how large my circle of friends and family would grow after I opened those first doors,” Waggoner concludes.

John Burgman is the author of High Drama, a book that chronicles the history of American competition climbing. He is a Fulbright journalism grant recipient and a former magazine editor. He holds a master’s degree from New York University and bachelor’s degree from Miami University. In addition to writing, he coaches a youth bouldering team. Follow him on Twitter @John_Burgman and Instagram @jbclimbs. Read our interview Meet John Burgman, U.S. Comp Climbing’s Top Journalist.