In early 2020, as the reality of the global pandemic began to set in and gyms started closing their doors, many climbing coaches were forced to rethink the ways in which they could ply their craft. Many lost not only a facility to work from, but also client lists and contact information. Their understanding of coaching was predicated on face to face interaction, and with the boom of the climbing gym industry, there was no reason to doubt that―until a reason revealed itself.

In 2015 I took my coaching entirely remote, so in March of 2020 I found myself and my business, Power Company Climbing, in a unique position from which to navigate the lockdowns. The switch to at home workouts for our clients was a simple one. We were able to offer free home sessions to thousands of climbers. Even while making an effort not to capitalize on misfortune, we had our biggest months ever.

But can it possibly be an effective way to coach climbing? As a former gymnastics coach who worked with athletes entirely in person, I also had my doubts. A few of those doubts, five years later, have been confirmed. However, most have entirely disappeared, and in some cases have been replaced with surprising clarity. In fact, from my vantage point, the most common reason why remote coaching for climbers must be ineffective has been absolutely flipped on its head.

“Climbing is a movement sport. It’s impossible to coach it remotely.”

You aren’t wrong about climbing. First and foremost, it does revolve around quality of movement. But instead of immediately asking if it can be effectively coached remotely, let’s first examine how climbing movement is learned.

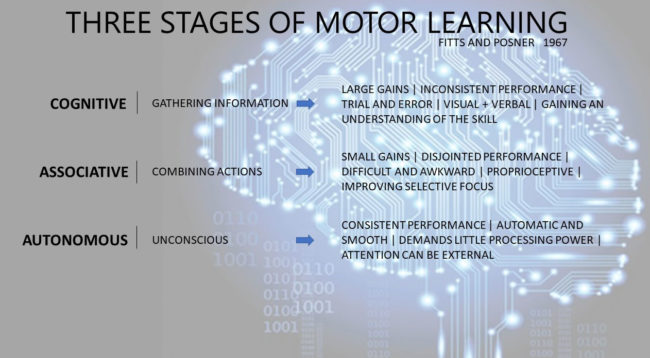

While the field of motor learning is wide and can be difficult to wade through, as climbers and climbing coaches we can benefit the most from starting at the classic theory posed by Fitts and Posner in 1967 in the book Human Performance. The theory asserts that performance is characterized by three sequential stages, termed the cognitive, associative and autonomous stages.

The cognitive stage is essentially the beginning of a new skill. The learner is gaining an understanding of it through trial and error and can experience big gains in that understanding. Next the learner enters the associative stage, in which they are able to focus attention on specific details and can begin combining actions, often resulting in the performance appearing disjointed and awkward. This stage shows generally small gains.

The final stage of learning is the autonomous stage, in which the skill becomes more consistent and smooth. Because the skill has become more automatic and demands little processing power, the learner can focus their attention externally. For example, once the driving through the hips and legs and maintaining of tension have become automatic, it becomes far easier to focus on the specific part of the hold you need to hit in order to stick a move.

“More rhythm!”

I recently watched the documentary I Am Bolt, which follows sprint legend Usain Bolt as he prepares for the 2016 Olympic Games. In the training scenes, I recognized a distinct lack of technical coaching. “More rhythm,” his coach shouted repeatedly.

“More rhythm!” That’s it. The greatest sprinter the world has ever known, preparing for a historic race, and that’s the technical breakdown of his stride from his coaching staff.

The best coaches often say less. That’s because for athletes (or anyone for that matter) to learn, they have to struggle with it themselves. Moving through the three stages of motor learning takes time and effort.

When I work with other coaches, by far the most common error I see is giving too much input. We feel like our job is to point out every way a move could be made “better.” Or even worse, to repeatedly give beta in an effort to accelerate success. Instead, by handing out solutions and overwhelming the climber with things to “fix,” we’re often stunting the learning process―cutting short one or more of the stages of motor learning.

A blessing in disguise

It turns out that overcoaching is incredibly difficult when you aren’t actually watching the entire session. That can be a good thing.

While we’re more apt to jump in and offer suggestions in person, remote coaching allows the climber time to process on their own. To grapple for solutions. To struggle at making the connections. To activate the neural pathways that allow a lesson to “stick.” In many situations, the fact that we can’t give input in the moment is a blessing in disguise.

Of course, the fact that remote coaching can work doesn’t mean it is a hands-off magic bullet. Coaches still need to provide appropriate feedback and support, which will change from climber to climber. We will have to ask climbers to repeatedly go back to the drawing board. They’ll likely get frustrated. So will you.

Remote coaching also will never take the place of a great in-person coach. A keen eye with a penchant for balancing struggle with success while asking the right questions, will always be the best way to learn advanced movement. More rhythm!

Kris Hampton is a climbing coach and owner of Power Company Climbing. He’s climbed 5.14 and V double-digits, but gets more satisfaction from seeing the progression of the climbers he works with. Other than his life-long love of hiphop, his current addiction is having face to face, in depth conversations for the Power Company Podcast and exploring thematic learning in climbing progression. You can learn more at powercompanyclimbing.com.