By Chris Rooney

It used to be that climbing gyms were more comparable to dungeons than to fitness facilities. The typical bouldering gym was a passion project, built by climbers for climbers to facilitate a lifestyle centered on climbing outdoors, not on indoor bouldering or sport climbing. Don Robinson, the UK man widely credited with developing the first artificial climbing wall, invented the concept because he noticed that outdoor climbers had no way to train during the winters. Subsequently, climbers experienced a high likelihood of injury upon returning to the crags when the weather warmed up. The primary goal was not on creating a growing investment that might lead to a financial return in the future. Even seeking to receive a return on investment in your climbing community might be seen as anathema to many “former dirtbags”, who traditionally subscribe to a culture wholly at odds with corporate interests.

But now, the industry is seeing an expansion in the kind of palatial indoor-focused gyms that attract a huge number of urban professional and family-oriented nonclimbers. The climbing gym industry has grown at an unprecedented rate in the past several years. In 2014, 29 new climbing facilities opened (9% growth over the previous year); in 2015, 40 new facilities are planned. Yet in the past three years, only 8 out of 353 commercial climbing facilities in the United States have been sold or acquired. While the indoor climbing market has grown, it has not reached the point of a robust buying and selling market for facilities, and the industry hasn’t seen many owners of large gyms exit their investments.

At the current rates of facility growth, Johnny O’Brien, cofounder of High Point Climbing in Chattanooga, Tennessee, expects to see a robust buying and selling market emerging sometime in the next ten years. “I think there’s going to come a point in time when people all of a sudden are going to start acquiring gyms, but there haven’t been a lot of acquisitions yet in the industry.”

In many industries, creating and executing on an exit strategy is a crucial part of the business plan. For a typical business, the exit strategy is a set of methods or contingencies that allow the business owner to mitigate future obstacles in the market, retire, sell the business, or move on to other projects. An exit might take the form of an acquisition, merger, or even an initial public offering (IPO). A certain amount of exits in an industry are an expected component of the natural “lifecycle” of an industry. Having a clear exit strategy in some ways is equivalent to having a clear goal for the business; creating value for the business’ sake will eventually bring it to the point at which it’s a viable candidate for acquisition by another facility or new gym owner, hopefully for a price greater than the initial investment.

The Industry Life Cycle

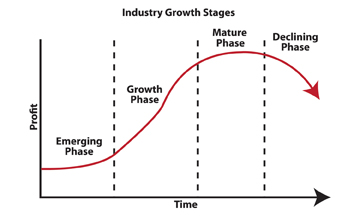

A typical business lifecycle consists of 4 general phases: an emerging phase, growth phase, maturity phase, and declining phase. In an emerging phase, new businesses and business models are developed in a burgeoning industry, with a market usually experimenting on the success of several different models or offerings. In a growth phase, revenues continue to grow, profit margins increase for certain products or businesses (or don’t) and competition increases, with new businesses entering the market all the time to take advantage of a growing market. In the maturity and declining phases, new entrants to the market slow down due, in part, to saturation of a market and slowing growth of revenues and profits (or declines, in the case of a declining phase).

Exits like acquisitions usually begin to come into play during the growth phase, in which new products or facilities are built at an increased rate, the customer base grows rapidly, and competition tends to increase. In an industry like healthcare, exits occur regularly: if a business is profitable, it can be sold, because the industry has matured enough to have evolved proven business models, and the mergers and acquisitions community has a deep understanding, based on past experience, of how that business might perform in the future. For a business model based on a physical facility, such as a climbing gym, the number of facilities in the market factors into the exit strategy as well—it can make more sense as an potential business owner or investor to buy or invest in an existing business than to develop a new one in a market with many existing options.

But in industries that have not yet reached maturity, like indoor climbing, the investment community will not yet have an experienced understanding of a viable business model for an indoor climbing facility. In addition, the principles by which these facilities are valued are still being established, especially given the ongoing growth in participation from new climbers and fitness enthusiasts. According to O’Brien at High Point Climbing, the climbing gym industry hasn’t standardized these principles of valuation like more mature industries have. “As you see profit margins increase, and in ten years you see a lot of people climbing, and gyms are profitable, and there are acquisition opportunities – that’s when I think you’ll actually get to the point where developing valuation principles that are applied to gyms happen like in any other industry,” said O’Brien.

Some of these “valuation principles” are obvious: healthy profits, high value of physical assets, and a growing and loyal community of gym members. Growing membership, in particular, strongly indicates higher profit margins in the future. Others, including key employees like routesetters and instructors, local gym competition, the importance of a climbing facility’s location, and the value of similar facilities are simply still being established. For example, the cost of maintaining a facility that is both convenient and has the customizable space required for climbing substantially affects the value of the business.

When these valuation principles standardize in the industry, it will become much easier—and more common—to acquire and exit successful gyms. But what can gym owners do now to prepare for the future of the climbing gym market?

For Sale?

According to John Hawkey’s Exit Strategy Planning: Grooming Your Business for Sale or Succession, understanding the future value of your business is a fundamental tool for determining the timing of an exit, particularly for determining the cost/benefit ratio of selling now versus in five or ten years’ time. When it becomes clear that a business will be more valuable at a future date, gym owners incorporate that into their exit plans, and thus do not exit until they can maximize the value of the business.

Alternatively, if the business’ value is projected to decrease in the future, then the owner has a compelling case for exiting sooner than later. Some of these industry-specific factors are still being developed in the climbing gym industry, but while participation in indoor climbing continues to grow, the future value of these climbing facilities is reliably projected to increase on their current values. “I would hope that in ten years, that there’s been some consolidations and buyouts, and perhaps we’ll have our first public company in the market out there,” said O’Brien.

Wide Open

Many markets in the US have also not yet been saturated with facilities of every type, from sprawling indoor climbing and fitness gyms to tiny outdoor climber-focused training gyms. The gym industry is heading rapidly towards a diversification of climbing options in any given market, with large facilities like High Point Climbing, focused on climbing as a component of a fitness-based lifestyle, acting as alternatives to smaller training gyms with communities primarily training for the outdoors.

Due to the lack of indoor-focused options for climbing in many markets, right now it’s a better investment to develop a large new gym – with a higher future acquisition value – than to acquire an existing facility.

Interestingly, while the early gym owner’s inner “dirtbag” may have originally avoided selling the facility to maintain their climber cred and lifestyle, now the industry is moving towards a point where the growth in clientele is coming not from current outdoor climbers, but from nonclimbers, families, kids and fitness aficionados, looking for facilities that are “family-friendly,” have youth climbing teams, and fitness classes like yoga. “The demographics coming into our gym are coming from a broad range, from kids, young adults; you’re seeing climbing teams being developed across the country,” said O’Brien.

By tapping into the customer base of the broader fitness facility industry, which had $22 billion in revenues in 2013 according to the IHRSA, a fitness and health club industry group, these large-format gyms are popularizing indoor climbing. Incorporating indoor climbing into mainstream fitness culture could potentially dwarf the revenues of the current indoor climbing industry in the years to come, leaving the door open for major acquisitions in the future. O’Brien sees this mainstreaming of climbing as a major reason for the current industry growth: “I think we’re on the right trend, because you see dynamic growth in the climbing gym industry itself, you’re seeing a lot of new development, a lot of new construction. You’re seeing a lot of the newer model gyms being built whether they’re full service fitness facilities included with the climbing element. And a lot of them are really becoming family recreation centers,” he said.

“And so I think we’re on the right path. It seems like we have a lot of momentum going right now in the climbing gym business, but we have a long ways still to go.”

Chris Rooney has been a Chicago-based climber for 7 years, and a writer for 3. Ask him for beta at @crooneys.

Climbing Business Journal is an independent news outlet dedicated to covering the indoor climbing industry. Here you will find the latest coverage of climbing industry news, gym developments, industry best practices, risk management, climbing competitions, youth coaching and routesetting. Have an article idea? CBJ loves to hear from readers like you!