By Trevor Russell

Picture 250 students gathered together on a Friday night, all doing the same thing. Do you think of the student section at a high school football game? Prom? No. Here, students dance up walls. In a climbing competition of Wisconsin’s High School Climbing League, teenagers socialize across teams, shouting encouragement. Fists pump in the air after successful sends. Forgotten chalk bags lie on bleachers. Everywhere there are team shirts full of word play, such as “Pirates of the Carabiner.” Voices carefully recite all the magic belay words in the correct sequence in order to begin climbing.

In recent years, it has never been easier to discover the sport of climbing. The chances of living close to a climbing facility in the United States have skyrocketed, with 300 new climbing gym openings in this country in the last decade, according to Climbing Business Journal. While that robust growth is being impacted this year by the ongoing COVID pandemic, there’s little doubt that climbing has been more in the public eye than ever.

But let’s not get carried away. Early this year I asked a class of freshmen to submit their dreams of the future. Amid the typically ambitious and touchingly idealistic responses were the requisite NBA, WNBA and NFL dreams. I questioned the class, faux-naively, “Doesn’t anyone want to be a pro rock climber?” Laughter. “Is that a thing, Mr. Russell?” Another asked, “Wait, can I get paid to climb trees?” The rejoinder: “If you want to be a lumberjack!” For many students, climbing is still not considered a “real” sport.

Around the country there are a few places, besides Milwaukee, that are spearheading scholastic climbing teams and clubs. Among the areas with an organized network of teams are Colorado; the Washington, D. C., area; Chattanooga and Knoxville, Tennessee; and St. Louis. The list is not extensive. But, multiplied all over the country, this model has explosive potential for exposing young people to an untraditional sport that many of them will love and can do for life.

The Start of an Adventure

Craig Burzynski, co-owner of Adventure Rock, the gym that hosts the teams in Wisconsin’s High School Climbing League, hatched the idea to start high school clubs about 15 years ago. “When I found rock climbing, really found rock climbing at the age of 19…it was like a respite from all the crazy stuff that I had going on as a young adult,” Burzynski says. “I thought if we can provide this outsider, but constructive, [activity] to do, that it would be a really awesome thing.”

Burzynski initially pitched the idea to a teacher he climbed with from a nearby high school. That became the first club; slowly more schools joined. In 2009, to develop it into a more structured climbing league, Burzynski hired an intern, Andy Miers, who later joined as a full-time employee. Miers had started climbing late in high school after he felt he had, based on his small stature, maxed out with football. Thinking about the barriers to entry of climbing, Miers says, “It was limited. You had to know somebody…to learn how to belay and how to tie knots.” Considering the missed opportunity of experiencing a league, he says, “I wish I had that when I was in high school. I wish I had had something that I could…turn to as a lifelong thing.”

The origins of the team I coach, Dominican High School, a Catholic school on Milwaukee’s North Shore, were students questioning traditional school offerings. Our team began where many good teenager ideas start: in a high school study hall. With four athletic students not yet playing a school sport. One of them, Bennett Artman, a freshman at the time with mental and physical energy to burn, has parents who had been serious climbers when they lived in Colorado years before. Both athletic and competitive, Artman disliked conventional high school sports. With a new gym opening not far away, he suggested forming a team. The others agreed, and the team’s eventual first captain, Colleen Fischer, already a little involved in the sport, was particularly keen on the notion. She asked me about being the adult leader, simply because I’m the resident outdoor adventure sports guy at the school.

Today, with an infrastructure in place and Andy Miers having ten years of experience helping to set up teams, Adventure Rock makes the process of starting a team easy. They offer a free day for students to try it out and a portable climbing wall on location to drum up interest. They coordinate weekly team practice times and give high school team membership discounts. And they organize and run the competitions.

Transitioning from a Club to a Sport

At first, the league was merely a loose confederation of a few clubs. Burzynski says, “We always started it from the idea that these were teams and the students were athletes, even though it was cluby, and at some point in time we got the understanding that a lot of parents had a hard time committing to having their children in this thing that they thought was a club because sports were more important.” In 2009, to increase credibility by branding it more as a sport, they decided to add competitions. “In hindsight that was probably the most brilliant portion of it,” he says, “because it changed the dynamic of what this was considerably.”

Although for a few years the competitions were more small group hang-outs, the athletes got culminating events to organize the season and test themselves. But parents would show up to spectate, which got them more behind it, leading to more school support. After about four years of development, some of the participants began to get very competitive. Still the model remained “big tent”—a place for everyone.

“Our focus for the comps,” Miers says, “is how are we going to…open it to as many kids as possible? How can we make this easy and as unintimidating as possible?” Adventure Rock’s goal was to bring in climbers—youth that are already into the sport—and youth looking to experiment, those looking for a social activity and community, and those wanting something fun and casual. The competitions allow them to select their level of seriousness—”challenge by choice”—ranging from looking at it as another night of climbing with friends but with greater team focus, to butterflies in the stomach tense. The strict “You’re going to run ‘til you puke!” coaching style of my high school football coach would be out of its element here. With the goal of inclusiveness in place, Miers says, “Once we broke the 120 mark at a comp, we were like, ‘Oh my god!’” The biggest competition this past year had about 275 participants.

A Chance to Excel and to Be Recognized

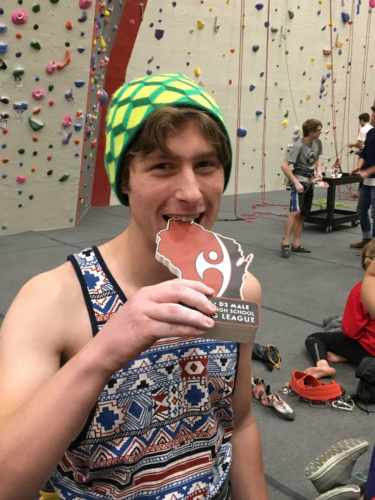

Fast forward to last year’s state finals competition, an on-sight format that Adventure Rock organized and presented with the hype of a USA Climbing event. Two hundred and fifteen athletes from the climbing league’s 23 teams squared off.

One of those students was Gavin Olig, a sophomore who had been climbing for two years. Although very athletic, Olig hadn’t competed in any other high school sport—only training for parkour on his own. He was searching for another sport when he chanced upon climbing at a summer camp. That experience sent him to Adventure Rock in Milwaukee. From the gym he got the idea to begin a home school team, a team that’s regularly in contention for the team title.

Olig is one of many success stories of the Wisconsin High School Climbing League, in his case of a teenager who found both a new sport and personal affirmation in climbing. In the state finals, with the crowd holding its breath, he on-sighted a 5.12, winning the highest division. “Finishing that route was amazing, basically the best feeling ever,” he says. “It was really cool to see that all my hard work paid off.” Being good at something may be its own reward, but many people want recognition—to be good in public and to be acknowledged for their excellence.

Bringing Individuals Together

Still, for many team members, the competitions are the least important component. They like climbing; they love how social climbing is. Olig too notes, “There’s a lot of sitting around on the mats exchanging beta, just hanging out…Some of my best friends I made through the team. And I’ve made a lot of friends on other teams.”

Others love the individual aspects of climbing. Paul Manley, another student on my school’s initial team and a senior at the time, went into it reluctantly and unsure. A risk-free trial day at the gym for our team whetted Manley’s appetite enough to commit. Within a week, he says, he was captured by the sport, and two weeks after that he was already a certifiable gym rat, climbing three to four days a week. A person who thrives on a challenge, he won two competitions within the first six months, advancing to the highest division. The individual facet of the sport helped him thrive. “I just don’t like relying on a team…but climbing, it’s based on how much I want to put in,” he says. Now a graduate, he helps to coach our team.

Similarly, Artman fell in love with the sport because, in his words, “you’re by yourself; it’s only you on the wall, and this is infatuating to me.” Last summer he competed at junior nationals in speed climbing. More interested in rock climbing than climbing competitions, Colleen Fischer puzzled her art teacher by repeatedly drawing and painting pictures of El Capitan and Zion big walls. She was able to recite, to the minute, how long it takes to drive from Milwaukee to Yosemite.

A Sport for High School and Beyond

Climbing is a sport that stimulates dreams of adventure. Miers says, “I think one of the coolest parts [of the climbing league] is seeing students…choose where they go to college based off what rock is in the area, so watching kids go to Boulder or out to Utah or California…It’s been cool to see how that’s changed lives.” It’s not a college scholarship or bust. Seeing Olig descend from the top of his successful send in the finals, pumping his fist in the air in celebration like in other sports, you can’t help but think about what other youth are missing.

One thing that they’re missing is a Friday night gym full of climbers cheering teammates on in competitions. Fifteen year olds performing powerful moves on sick looking boulder problems. An announcer, hamming it up, will introduce the next climber in the finals, saying, “Next up for division two girls, the Captain of Crimps, the Sultana of Slopers, just in from her world tour, it’s Katie Smith!” Pewaukee High School’s team of about 35 climbers will form a tunnel to welcome and pump up their climbers who are entering the stage for finals. Then they’ll all yell, “P-K-E!” followed by a single loud clap. Kettle Moraine High School’s team of about 40 climbers will do their in-unison “Chop! Chop! Chop!” cheer for its climbers, while they all chop the air. Whatever it signifies, it stirs up the crowd. Burzynski will grab the announcer’s mic, egging on other teams: “Dominican, where’s your team cheer?” The events bring individuals together, promote an overarching community, and create one more opportunity for young people to thrive.

Trevor Russell lives in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and teaches at Dominican High School. Besides misbehaving children, including two of his own, what quickens his pulse is music, coffee, downhill skiing, mountain and road biking, and, of course, rock climbing.